Hi all. I have been practicing a lot. Got lots of new stuff to tell, and Lord only knows when I’ll have time to blog it. Here’s today’s thing: Ted Eschliman’s FFcP (Four-Finger Closed Position) fingering system. I learned about it at jazzmando.com/ffcp_studies.shtml

(The FFcP system described on that page is intended for the mandolin, but it works well on the banjo too.)

Let’s look at a major scale:

It has eight notes. Since we have four fingers to use on the fingerboard, it makes sense to divide the scale into two halves:

These four-note successions are called “tetrachords”. Tetrachords are the basis of the FFcP system. Check out the whole-steps and half-steps. They are the same for both tetrachords!

F to G: a WHOLE step

G to A: a WHOLE step

A to B♭: a HALF step

C to D: a WHOLE step

D to E: a WHOLE step

E to F: a HALF step

This WHOLE-WHOLE-HALF pattern is always the same for major-scale tetrachords.

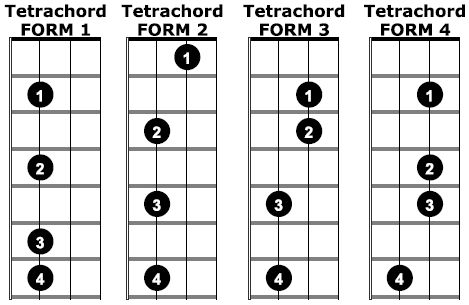

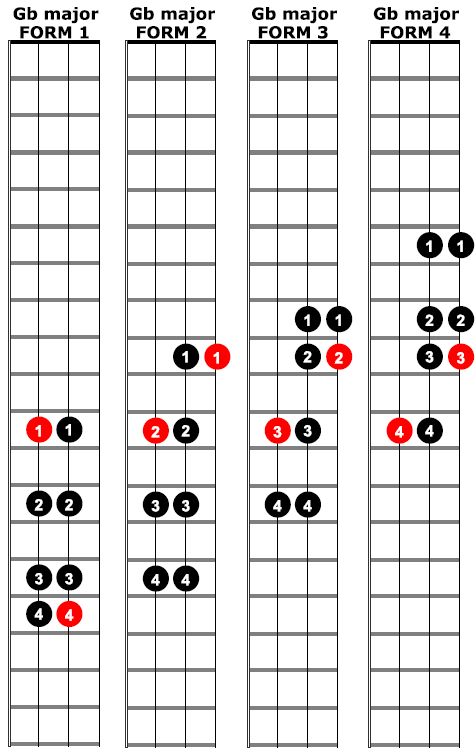

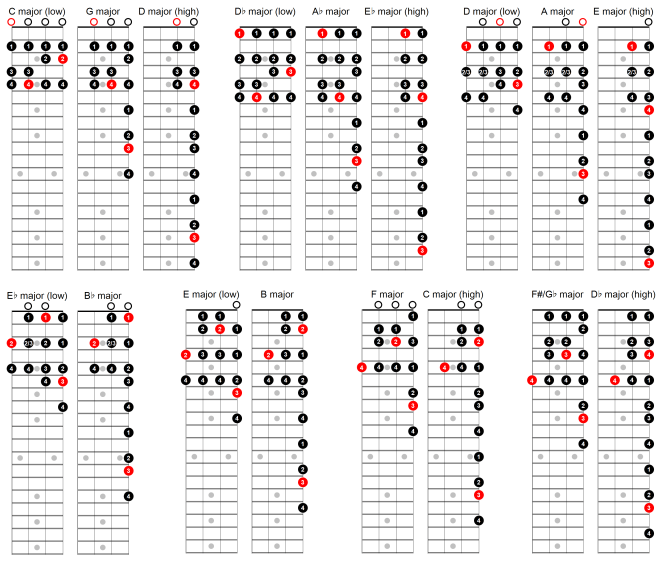

Now, here is the genius of the FFcP method: There are only FOUR ways to play a major tetrachord on the mandolin or tenor banjo:

Do you see the WHOLE-WHOLE-HALF pattern in each one? It’s most obvious in Form 1.

By the way, each of these “Forms” can be moved around to start at ANY fret on ANY string, as long as it’s not too low or too high for all the fingers to fit.

Why is it so important that there are only these four “Forms”? Well, if you learn them — which is an easy task — you can play ALL the major scales without learning ANYTHING else!

This is very different from most other instruments. On the trumpet, for example, you have to learn a completely different fingering pattern for each scale, in each octave. To learn all the scales from low F# to high D, you have to learn 21 scale patterns. TWENTY-ONE! And each pattern has EIGHT notes, whose fingering has no immediately discernible logic. You just have to learn all the damn scales, one by one, over a period of years.

On the tenor banjo, you just learn FOUR different tetrachords (“Forms”), and each one has only FOUR notes. Much easier! Try fingering each one of them on your banjo, at different frets and on different strings. Give yourself a few minutes. Some of them will be easier than others. I personally find Form 4 the most natural and Form 2 the most uncomfortable.

. . .

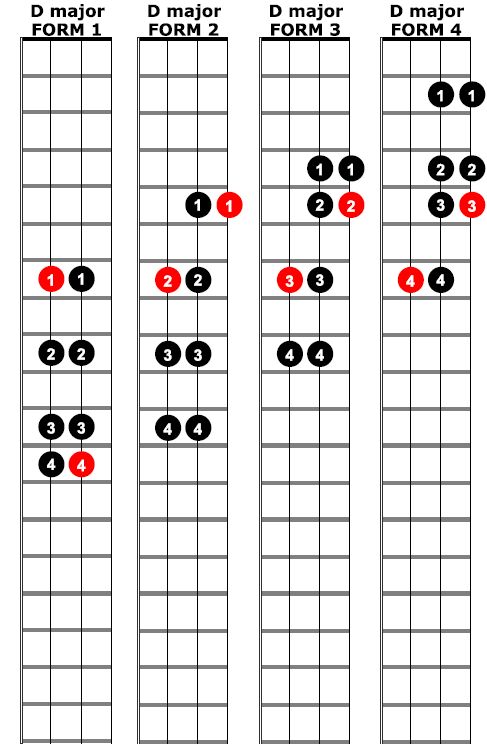

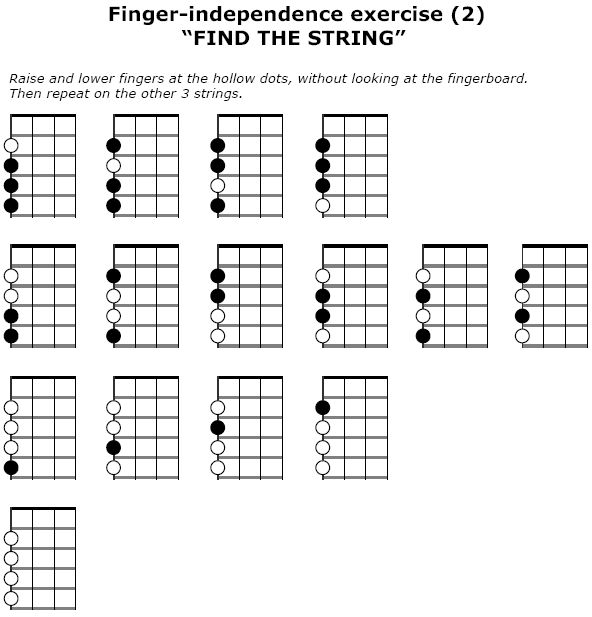

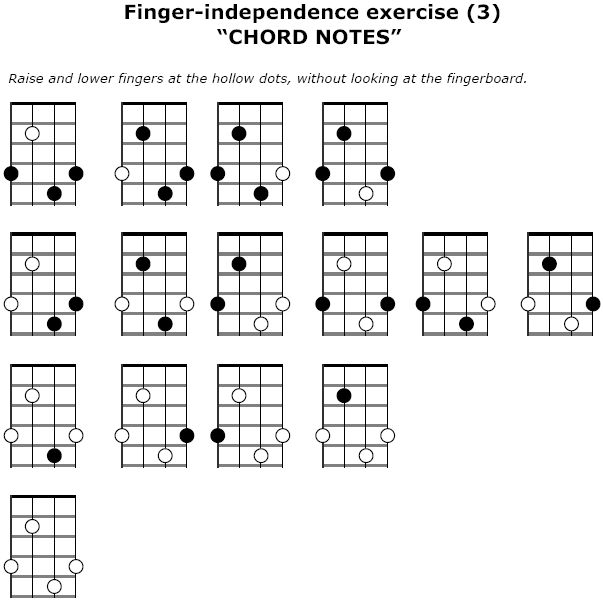

Okay, now that you know how four basic tetrachord Forms feel, let’s use them to create a major scale. You just finger each form twice, and, voilà, you’ve got a major scale! Here they are in D major. (I’ve marked all the D’s in red.)

Try them out, again varying the frets and strings you use.

. . .

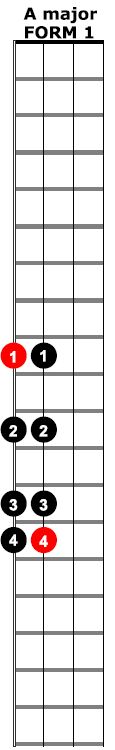

Remember, you can use any of these four Forms for ANY starting note. So, for example, if you want to play a low A major scale starting with the first finger, you would use Form 1, starting on the first string at fret 7:

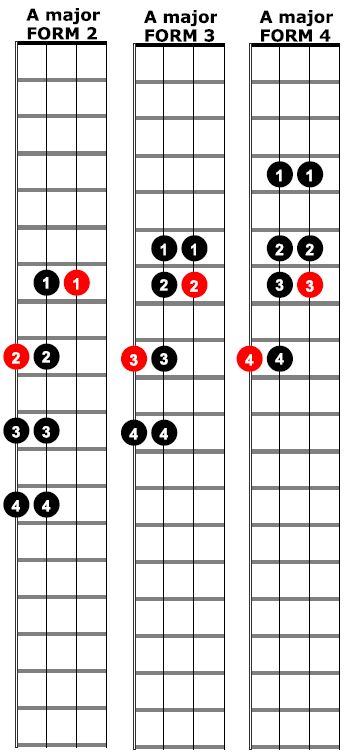

If you wanted to start with the second, third or fourth fingers, you would use Forms 2, 3 or 4:

Notice that in each of these cases, you start on the same string and fret. The only difference is which finger you use to play the first note. This determines the Form you’ll use. Try them out!

. . .

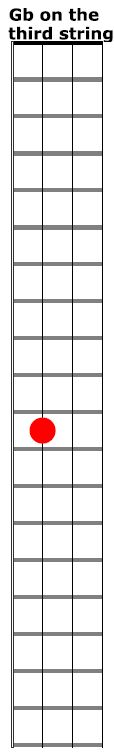

You can do just the same with any other scale. Let’s play a high Gb-major scale. Your starting note will be Gb on the third string, 11th fret:

Decide which is the best Form for the sound and fingering you seek. In this case, all other factors being equal, I believe that Form 4 is a good combination of sound quality and ease of fingering:

Try them out yourself — all four Forms, not just one or two. As I mentioned before, some of them will be easier than others. Also notice that some of them SOUND better than others. The ones that are near the nut generally sound more resonant and “banjo-like” (i.e. better) than the ones that are close to the bridge, which can sound rather tubby and characterless.

Fiddle around with these scales for an hour or two, and I guarantee that you will find it time well spent. I certainly have!

. . .

If you’ve followed the above explanation, you might reasonably have the following questions:

- How do I decide which note to start on?

- How do I decide which Form to use?

- What about scales with open strings? Where do they fit into this four-Form system?

But I have to stop for now. I hope to address these questions in my next post. See you soon….

I wouldn’t be without it.

I wouldn’t be without it.